Quiet Rage and the Limits of Mountains

Four hours passed before the sun began to rise at 17,000 feet, and I tried to make peace with the boa constrictor coiled around my head. With cold, stiff fingers I dug out a frozen protein bar, inhaled deeply, and crammed half of it into my mouth where it clung stubbornly to a sandpaper tongue. Despite the persistent lurches of a stomach eager to empty itself, I knew I needed the calories, so I gagged down the chocolate-flavored dust, hoping not to throw up.

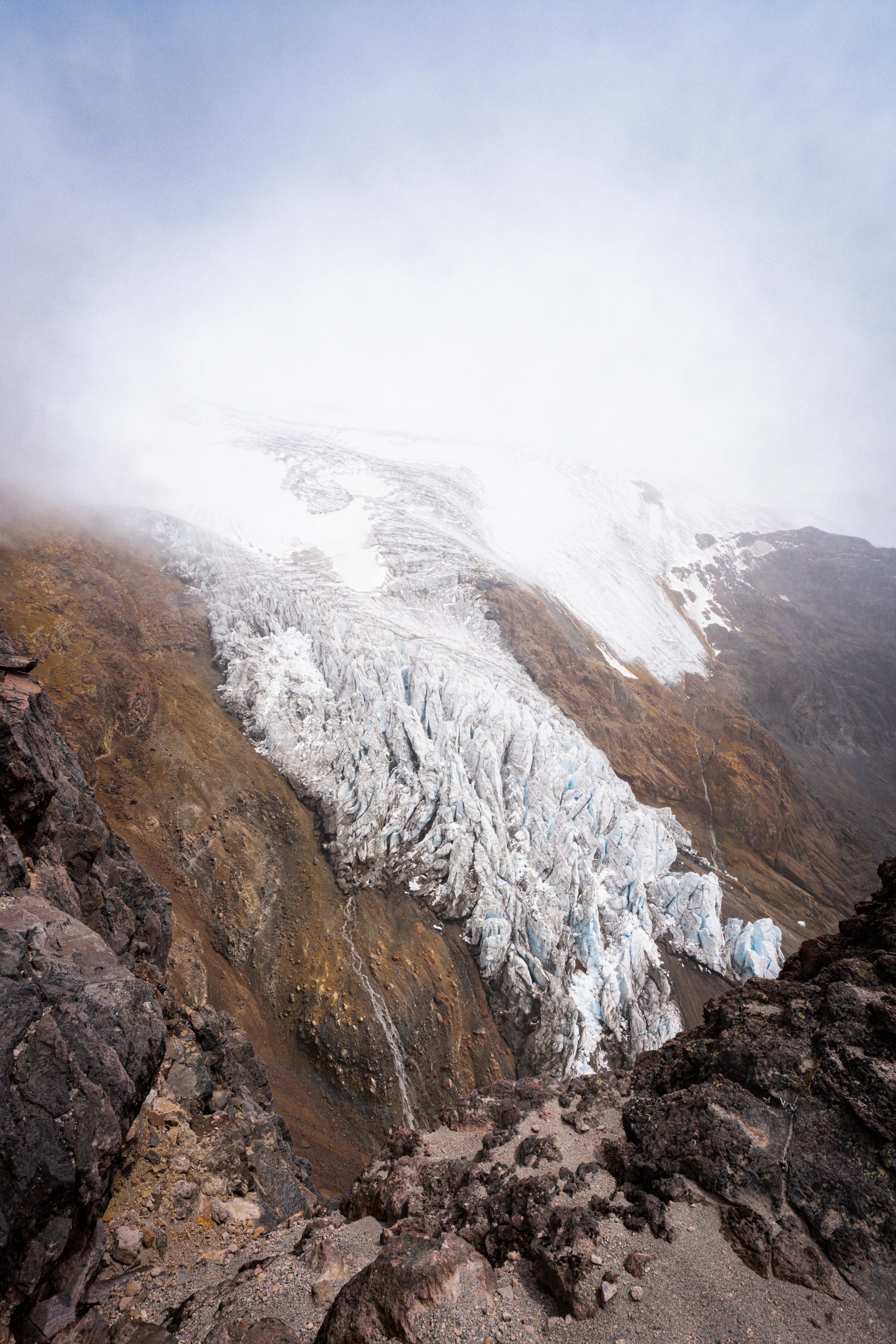

Below, the toe of the glacier was lost in a thick cloud that had formed a crust over my shell during the 90 minutes we’d spent skinning up from the edge of the moraine. The moisture that did not freeze pooled in the hoods of my three jackets, and every movement sent rivulets cascading down my arms and off the ends of my cuffs. Chilly predawn winds blew from the east. Around 2,200 vertical feet above the snowy bench where we sat loomed the true summit of Cayambe, Ecuador’s third-tallest peak at 18,996’/5,790m.

“How are we doing? Like, where are we out of ten?,” Sam asked once we’d started moving again. I’m sure he had a fair guess at how I might answer. Around 1:30 that morning, he’d given me one Motrin and half a dose of Diamox after I woke from a few hours of fitful sleep with a splitting headache and no appetite.

“6.5 out of ten,” I stretched. “Definitely feeling it. I can keep going.”

We set off toward the next bench a thousand feet up. Encircled in a sea of white, my conscience drifted aimlessly as thoughts grew indistinguishable from one to the next. The squeak of muddy pin bindings, the sschhhht of skins gliding up the track, the soft punch of poles in firm snow, and rhythmic, labored breathing scored our ascent. The rest of the team continued ahead more quickly, the distance growing between us. Every step felt like a greater effort than the last, and the landscape’s scale and uniformity made it feel like I was on a treadmill more so than climbing a mountain.

I thought about how thick the air would feel down at 15,000 feet, how warm the hut would be. Continuing up would mean thinner air, colder temps, and no relief from the ceaseless pounding in my head. But turning around could mean teeth-chattering, skull-rattling skiing through the dark, and the quiet, lingering disappointment of not having summited. Two voices warred within me, and either way, I was losing.

“You know who would be really proud right now?,” Sam asked rhetorically after half an hour of moving slowly up the glacier. I barely heard him, the sound of his voice pulling me from a spot I’d retreated to deep within myself.

My chest tightened and my eyes began to well, leaving frozen tracks down my cheeks. Before I could respond, he interjected: “Actually, I’m going to amend that. You know who is proud right now?”

A sound caught in my throat before the words “I know” could escape. I hadn’t thought about Aaron much thus far. These days, he prefers to visit me in quieter moments when I am alone in the mountains. But here, inexplicably, I felt warmth begin to spread from the center of my chest to the tips of clammy fingers and toes. The snake began to uncoil from around my head, and the nausea shrank. I didn’t understand, nor did I question how the altitude sickness subsided in an instant. My right hand subconsciously made its way to the place on my thigh where, beneath layers of polyester and GoreTex, a golden eagle is tattooed in his memory. Thanks, man, I thought.

Then, through the fog of emotions I still feel following Aaron’s death—grief, anger, guilt, admiration, gratitude—I heard his voice as clearly as if he were standing next to me. In his trademark way, he offered no traditional encouragement or reassurance, but instructions. A single word, imbued with all his lingering power.

Rage.

For better or for worse, this expedition to Ecuador was laden with emotional baggage. In 2018, I came here not as a climber, but as a student with no experience in the mountains and no intent to gain any. A last-minute, on-a-whim ascent of Cotopaxi (19,347 ft/5,897m) changed that, and I’ve spent the years since working to forge a viable career in the outdoor industry. Returning to Ecuador as a member of the Alpenglow Expeditions team was a tangible indicator that this plan might actually be working.

Three months prior to the trip, in September 2023, Aaron Livingston fell to his death while free soloing. In a sport and lifestyle where tragedy is not only common but expected, this was my first brush with death, and it took me by surprise and left me feeling shocked, robbed, and questioning the decisions that led me here. Worse, I lost an irreplaceable friend.

Amid the pride and satisfaction I felt to be here in Ecuador with Alpenglow, coupled with the pain of a sudden and tremendous loss, I also felt substantial pressure to perform and capitalize on the opportunity before me as a climber and photojournalist. But with a persistent comedown headache following after our acclimation lap up to 17,000 feet had me subconsciously questioning my mettle. The next day, I woke up on summit day in a depressive episode, on the verge of a panic attack. I didn’t understand how I could feel this way, so close to the most tangible realization thus far of everything I’d worked so hard for. I was discouraged. I was angry.

I laid on my back, eyes closed with a hand on my chest and another on my stomach, feeling the adrenaline course through me as I took careful, measured breaths. In the years since I first began suffering from panic attacks, I’ve learned that fighting the panic is like fighting a river - it’s a losing battle. With practice, I have learned how to keep my head above water by letting the fear flow through me. Instead of resisting, I acknowledge what is happening and cling to something—an image or memory of a safe place, a soothing song, or just something solid to grab onto until the panic dissipates.

This morning. I hung on for an hour until the calm returned.. Eventually, I was able to stand up, place bare feet on the cool stone floor, and press my forehead against the window. The upper slopes of Cayambe shone brilliantly in the morning sun, a rounded white pyramid vaulting up from the horizon.

The mountain doesn’t care, I thought, finding odd solace in its ambivalence. A gray wall of clouds swollen with moisture from the world’s largest rainforest hung low to the east. Soon the mountain would be engulfed entirely, and we would leave the comfort of our hut at Yanacocha to drive straight up the mountain and into the white room. This storm, and the one in my mind, would simply have to be weathered. Clattering plates and silverware from downstairs signaled breakfast.

⸻

It’s no secret that mountain culture celebrates a “play hard, stay hard” mentality, and I won’t feign innocence in perpetuating it. I play the role and I play it often: my job, in part, is to get people fired up to go to the mountains, to learn how to tolerate pain and discomfort in exchange for unparalleled outdoor experiences. When I’m not selling the product, I’m doing everything I can to live it. The mountains are a part of my professional life, but a deeper, humble admiration for the vast landscapes and a penchant for exposure are at the core of the personal and unshakeable love I hold for high places.

But there is a darker side to the rose-colored images that permeate the outdoor industry, one where the wars we wage within ourselves are hidden away beneath the shadow of the mountain. Online, I present an aura of constant positivity through wide-angle landscape shots and Insta-worthy adventure clips. And it is true that the mountains are where I feel the most aware of every part of myself - including the darker ones. But often, those things do not make it through the digital filter because talking about depression, or not being ultra-psyched all the time, can feel like pouring water on a fire that everyone is keeping perpetually stoked.

Back inside, the hut grew quiet as climbers retired with the setting sun. Some would begin the climb as early as 11 PM or midnight; we were shooting for 2 AM. Mantling up to a top bunk, I contorted my body and made myself long and flat to fit in the 12 inches of space between the twin mattress and the ceiling. I set my alarm for 1 AM and spent the next five hours mostly awake, listening to the quiet rustlings of my teammates, each of us battling for whatever sleep we could scrape together before it was time to move.

When my eyes slid open at 12:57 AM, I felt relieved that the waiting game was over, but was soon overcome by pain. I felt the snake constricting around my head with every heartbeat, my mouth bone dry, and the mere thought of food was nauseating. I’m here, I thought as I peeled my sleeping bag away from sweaty skin. I’m doing this. Just get up. After Sam dosed me with Motrin and Diamox, Ray shared that he’d spent the first five minutes of his day outside, in his underwear, just breathing.

“We’ve all been in here breathing the same air all night,” he explained. “The oxygen level is probably more like 30,000 feet in here. I know it sounds crazy, but go outside for a minute. I promise you, it works.”

After trying and failing to force down a hunk of bread, I was eager to do anything that might make me feel better. I kept my clothes on and ventured outside, noticing a shift almost immediately.

Maybe the Motrin and Diamox had something to do with it, but as soon as I stepped outside the change in setting and the stillness of the cool, more densely-oxygenated night air began bringing me back to life. I thought about stripping down for a moment until a stiff breeze suggested otherwise, and the idea that maybe I could manage something to eat coaxed me back inside.

At 2 AM, we hit the trail and began the long slog up the rock bands and sandy slopes of the moraine. The small hours of the morning passed quickly in the dark. It wasn’t long before we were skinning up the glacier, swallowed by an opaque moisture cloud. Shortly, I was trying to cram frozen bits of a protein bar into my mouth, Sam was asking me how I was feeling, and I was hearing Aaron’s voice in my head.

One of the things that solidified my friendship with Aaron was his vulnerability. If he was feeling low, he’d tell you. And as often as he was the one heckling you to harden up and do the damn thing, he’d also tell you to do it not in spite of your emotions, but precisely because of them. He showed the people around him how struggle builds strength. And so when Sam’s mention of Aaron melted away my headache and nausea, I made no effort to hide my emotions, and I wept. At the same time, I began to race up the mountain.

Sam suddenly appeared next to me and planted a pole in front of mine. “You’re charging, dude,” he cautioned. “Remember, slow is smooth.”

But the fire was lit, and the following hours slid by in dreams of blue and white, while the world around me fell away. Sifting through my memories to draw on their power, I slipped into a flow state, dragging one heavy boot in front of the other, hearing my ice ax pierce crunchy snow, and feeling the gentle tug of the rope against my harness. Occasionally I would remember to look around, noticing that the frozen landscape grew increasingly grotesque, malevolent, and otherworldly the higher we climbed. Then I’d look up the slope, pick some nondescript landmark, and say to myself, If I can just reach that heap of snow…

This is the unglamorous portion of high-altitude mountaineering that climbers who document their ascents often romanticize or gloss over completely for the sake of a more compelling narrative. But in truth, much of the time spent trudging toward the world’s higher reaches passes in this way. And while more technical and hazardous mountains present their own potent strain of suffering, the challenge of climbing non-technical peaks such as Cayambe rests in their inescapable monotony. It is a slow, passive form of torture made worse by the knowledge that it is, by all means, self-inflicted.

Regardless, something had changed and a wellspring of new energy powered every step toward the summit. I thought about how Aaron wanted to do these sorts of things—how he had done some of them—and how he would have wanted me to do this. As I wove my way around gaping crevasses, I thought of my family, and how badly I wanted to be able to make them proud, to tell them that I’d descended safely after reaching the summit. Fueled by all of the experiences that led me here, I looked inward and drew vitality from times of gratitude, joy, and friendship, as well as from heartache, grief, and loss. I let my body become a machine that converted emotion, any emotion, into fuel for the next step forward.

Traversing alongside a wide crevasse a few hundred feet below the summit, I peered down to see if I could locate the bottom. All I saw were white walls sinking into deeper and deeper blues, finally melting into an inky black. On a small flat above us, a stonehenge of skis indicated that the rest of the team were above us, making the final push to the top. Adding my skis to the circle, I heard Sam yell something that sounded like “two hundred more feet,” but in truth I didn’t know what he said, nor did I ask him to repeat it. The big mountains offer us a unique opportunity to take a hard look at what we’re truly made of, and I aimed to find out. Two hundred feet or two thousand, I was overwhelmed by a clarity of purpose, and had long since resolved to keep at it until my legs or lungs gave out.

As the time drew closer to depart for the high hut on Cayambe, I felt myself slipping into autopilot. Though I’d overcome the initial wave of panic, the experience left me feeling detached and apathetic about the climb. As Sam would soon be the one on the other end of my rope, I was obligated to let him know what happened.

“These big places,” he said, looking up toward Cayambe, “they can bring out big emotions, and they’re not always the good ones. You should think about asking Adrian [Ballinger] about it. There have definitely been times where he’s in the mountains and he’s going through it. Ask any of the guides. You’re not alone.”

Shortly, I found myself bouncing in the passenger seat of a loaded-down truck, pushing toward the mountain, mulling over Sam’s words. Light rain stippled the windshield and drifted in through the open windows during the 45-minute ascent to 15,092 feet, and the stone hut suddenly appeared through the mist.

Our team of thirteen unloaded a few hundred pounds of gear into the hut. Few words were spoken over the swishing of GoreTex, the whipping of jackets and packstraps in the wind, the hollow clap of plastic ski boots knocking against one another, and the thud of heavy feet on crowded wooden stairs. For me, and I suspect the rest of the team, reality was sinking in.

Inside, the hut buzzed with a quiet energy, the challenges and risks that lay ahead ever present in our minds. We all wanted to make it to the top—but how we do it, why we do it, and from where within ourselves we draw the strength to do it is singular to each climber. Hushed tones and quiet nods evoked an air of mutual respect unique to these high places.

Outside, a brilliant sunset bathed faraway Antisana’s (18,875 ft/5,753 m) glaciated upper reaches with soft pink alpenglow, visible above a boundless blanket of clouds. The sounds of a dissipating storm mixed with the roar of ancient rivers in the valley below, on their way to the Amazon basin to the east. The primordial nature of this landscape, massive in size, scope and ecological diversity, humbled me with an almost religious feeling. Places like this remind us how we are the result of billions of years of cosmic, organic evolution, the conscious universe looking back at itself.

Protected by a handful of blue-mawed crevasses, the summit plateau of Cayambe curves softly upward until leveling out to a nearly-flat expanse of perhaps half a football field. In the middle is a hump of snow and ice, perhaps 20 or 30 feet tall, which is the true summit of the volcano. From the edge of this field I could just make out the flickering colors of the team clambering down from the top.

“Drop your pack here,” said Sam, 20 yards from the final slope. “Let’s do it.”

Like a zealot I plodded toward the high frozen altar. Cresting the last ridge with no place higher to go, I fell to my knees. On all fours, black gloves pressed into the snow, with quivering limbs upholding a body that hardly felt like my own. A wave of relief washed over me, and all was silent but the wind. I felt both more exhausted and more alive than I suspect I ever had. A strange heat filled the space between my eyes and foggy lenses, my breaths were stuttered and uneven, and I realized I was sobbing. I rolled onto my back and let the tears flow, cracked lips spread into a wide grin as I gazed into the blurry blue.

Five minutes later, I stood up, threw on my pack, sunk the hilt of my ax into the slope, and began the descent.

There are experiences in life that lead to fundamental changes in who we are and how we view ourselves. It isn’t often we see them coming, or even realize it when we’re in them, but we hopefully recognize them when we come out the other side. My experience on Cayambe was one of them.

When I first heard the term ‘rage’ tossed around in the climbing world, I understood it to mean something like power-screaming at the crag in a show of anger, strength, and survival instinct. It was something loud, flashy, ostentatious, and suggested a sense of urgency and immediacy needed to pull through a hard move. Cayambe taught me that rage can be quiet. It can be slow, patient, deliberate and, when carefully tended, used to access a flow state. Rage, in this sense, is simply a way of referring to what we may otherwise call the vitality of the human spirit, a harnessing of all the experiences and emotions that make us who we are, and the notion that they can be a source of infinite energy. Embracing vulnerability and opening myself to this form of quiet rage, I felt closer to Aaron in death than I ever did in the year I knew him in life. I felt closer to myself, too.

Overall, I am left with a prevailing sense of gratitude. Cayambe forced me to shift my thinking from “I’m in the big mountains, I should feel happy,” to more intimately understanding what the mountains can and can’t do for me, and accepting that adventure is not a universal antidote. It forced me to reevaluate my relationship with extremes, and see that the reason I seek them is not to find happiness, but clarity. After weeks of reflection, I’ve determined that while the mountains may not directly offer the help I need to take control of my mental health, I see more lucidly than ever that I owe it to myself to keep asking for it.